evolution of clocks

what clock properties evolve under natural selection in the laboratory?

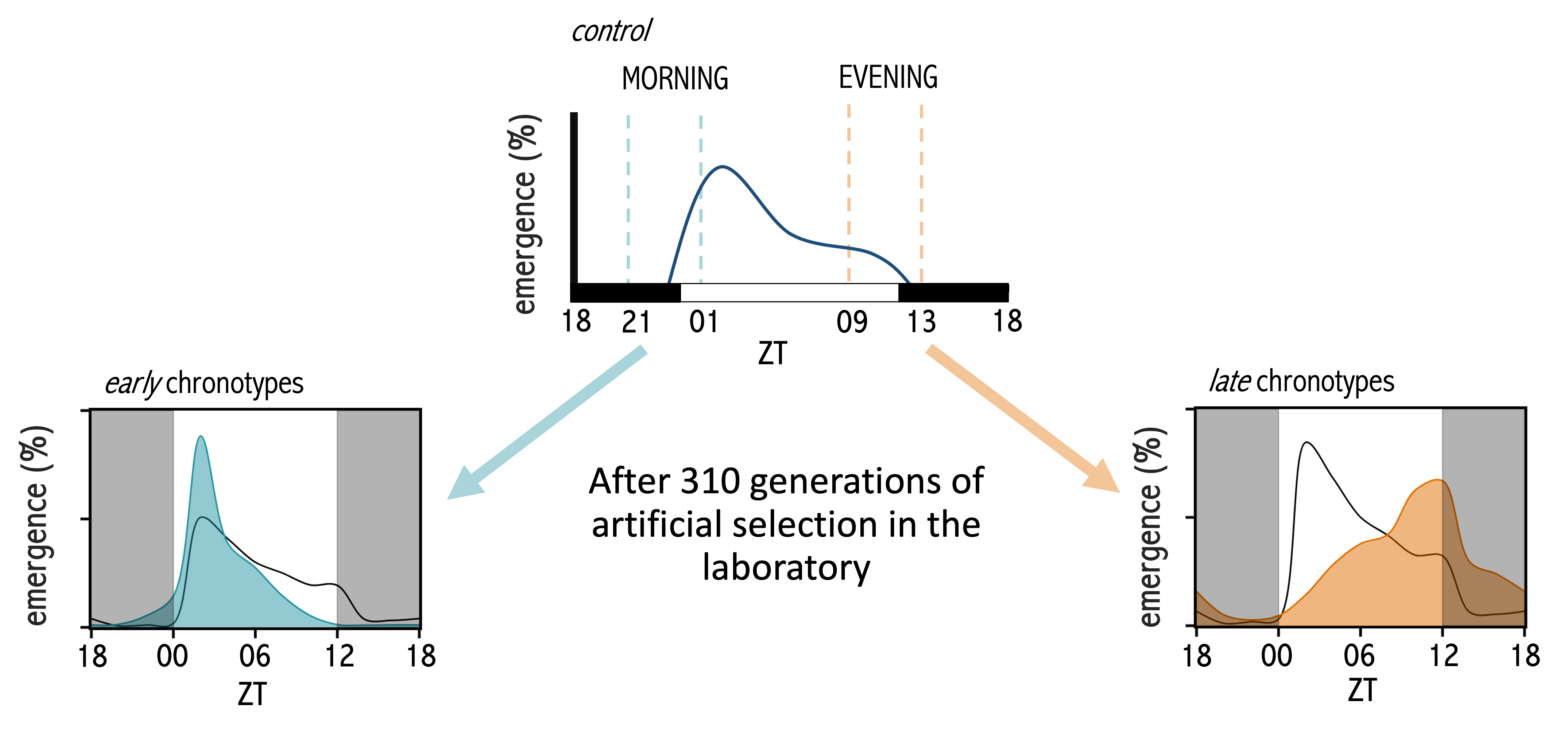

I’m sure everyone is aware of what chronotypes are. You may not know the term, but you know that there are “morning” people and “evening” people, right? Morning types are people who go to bed early, start their days early as opposed to the evening types. These are what we refer to as chronotypes, in the chronobiology jargon.

Such preferences are driven by our internal timers and are, to a large extent, heritable. While we know that such chronotypes exist and there is a wide distribution of these preferences, and that they are driven by our internal clocks, the properties of clocks associated with such chronotypes is a little less understood. Genetic constraints that drive the evolution of such preferences have been unclear and that’s what I spent my M.S. and Ph.D. trying to address.

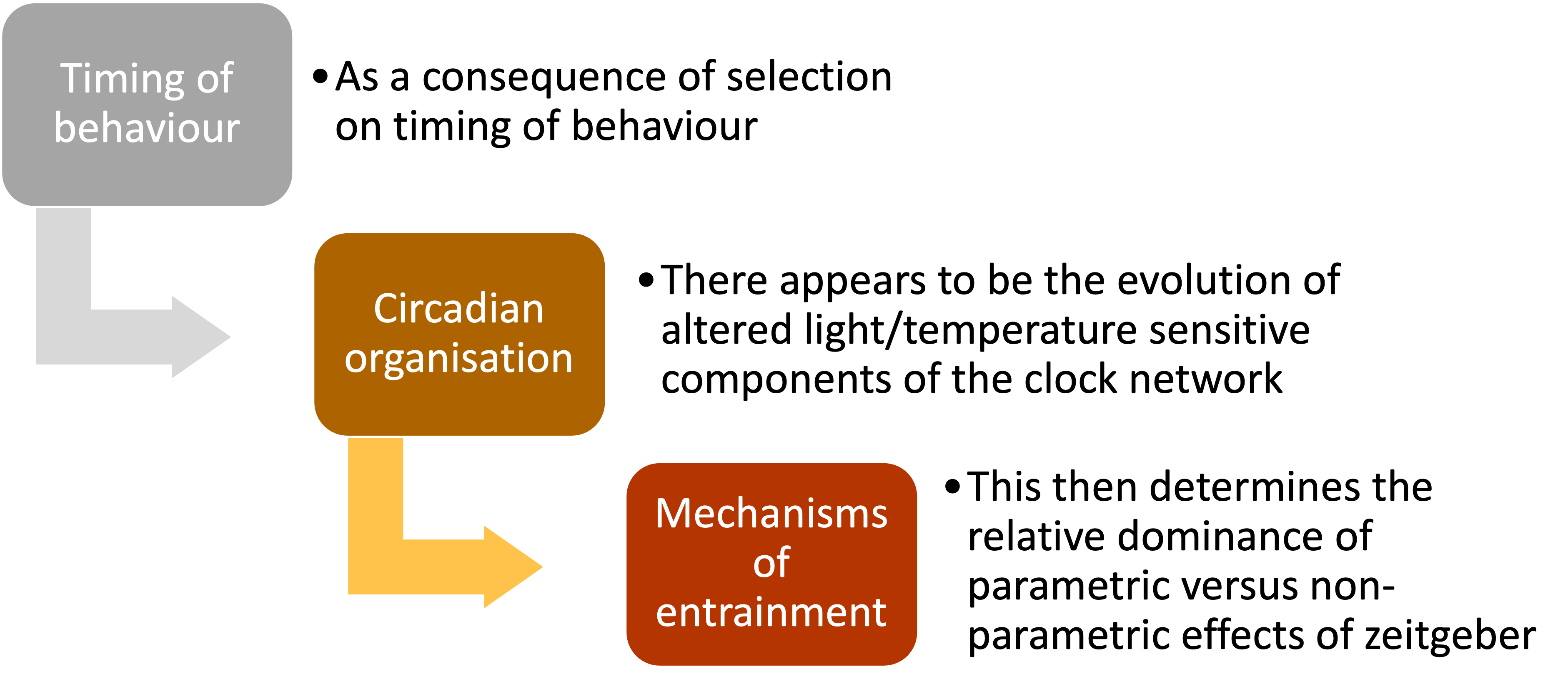

To get at the heart of this problem, we use Drosophila melanogaster populations. These are small insects that are also known as fruit flies or vinegar flies and you’d have seen them hovering over slightly over-ripe fruits that you leave by the window or on your dining tables. What we did as a lab over the last 30 years or so is impose selection (as in Darwinian natural selection, but in the lab; see above) on timing of behavior and document how properties of circadian clocks change as a correlated response to evolution of timing.